This is one of those rare times when the fact that this column has to be written nearly a week before anyone can read it is causing me enormous difficulties. I hate to make predictions about the near future when they can so obviously be totally wrong almost by the time the ink is dry but for once I will take the risk rather than write about some timeless issue, like the slow progress of European signalling systems or the counterproductive behaviour of the RMT, because these are such interesting times.

The new government has so much on its plate in relation to transport and, specifically, the railways, that it is not surprising that amid all the leaking about HS2 and franchising, nothing concrete has yet emerged. So let’s try to work out what is happening. Note, first, though, that Johnson inherited a massive roads programme and there is little sign that he is planning to rein back on that, despite the fact that transport professionals the world over know that it more roads usually lead to an increase in congestion unless mitigating measures, such as tolling, are taken.

The franchising system is falling apart in front of our eyes with Northern already about to be removed and South Western in a stricken state, which follows the renationalisation of East Coast last year. Jeremy Corbyn may have lost the election, but he must be having a chuckle about the gradual renationalisation of the railways being undertaken by his opponents.

This increasingly chaotic state of affairs means that the Williams Review which was set up as a quick and dirty process in, euh, September 2018, has to produce results very soon. In fact, it is widely expected, as I have mentioned before, that its recommendations (Williams may be independent but the review is not) will be in the form of a White Paper, setting out firm intentions by the Government rather than initiate a consultation process since Williams has effectively already undertaken one. There is now widespread consensus in the industry that the government is going to recommend changing the franchise system into a series of management contracts but precise details remain to be sorted out.

The big difference will be that the private companies taking on contracts will no longer have the revenue risk, just like currently with the London Overground. While the train operators are not happy about this, since they think it will reduce the incentives to expand the market and will mean less opportunity to make profits, the difficulties faced by several operators, together with the paucity of bidders has made this inevitable.

There is, too, widespread acceptance that there will be an organisation responsible for overall strategy in the railways, widely known as a ‘Fat Controller’ – I love the FT’s rather deadpan explanation of this expression in its editorial of February 3 which said ‘it was picking up a name from popular children’s stories’.

Devolution is in the air, too, as is vertical integration, and this is where any attempt to predict the outcome gets messy. If parts of Network Rail are split off to provide an integrated regional organisation, the issue of the huge debt owed by the company will have to be resolved. By the end of this financial year, it will have gone up to nearly £54bn (which, by the way, means that Network Rail and its predecessor Railtrack have borrowed more than £2bn annually, since the track and infrastructure was hived off from British Rail to pay for investment. This effectively represents an additional subsidy, bringing the annual total up to around £6.5bn rather than the usually stated £4.5bn). Clearly the government will not want that huge sum dumped on its books but there is no doubt that eventually it will be, saving Network Rail more than £2bn annually in interest payments.

Grant Shapps, our present transport secretary has been much on the airways, promising to foreclose on train companies that have not run services on time and suggesting that radical changes are afoot. However, Shapps does not seem to have grasped much about the detail of the rail system but despite being widely thought to be on the move survived the reshuffle and will now have to learn on the job. As for HS2, this is dangerous territory for prediction as an announcement could come very soon but my feeling is that the project is safe, though the delivery mechanism will need to be changed radically.

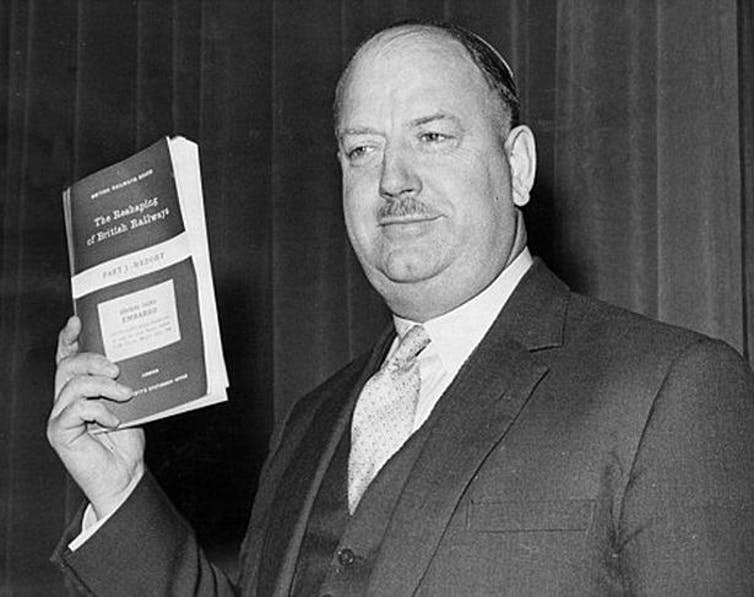

In the middle of all this news about fares rises and franchises collapsing, Shapps – or probably the No 10 media team – cleverly grabbed the microphone and announced that there would be a new £500m fund to ‘reverse Beeching’. Ah, this was so much easier than having to disentangle franchises and make decisions about the largest construction project this country has seen.

This was such nonsense that it is difficult to know where to start. The main new initiative was £20m for a new stations fund and a couple of specific grants were announced. As for the £500m, half was already in Network Rail’s budget and most of it will, in any case, go to towards paying for feasibility projects, with, according to the Department for Transport, the expectation that most of the funding to build lines will come from alternative state and private sources.

All much welcomed, of course, but it is hardly ‘reversing Beeching’. The reality is that there were 5,000 miles of lines and 2.300 stations closed as a result of Beeching’s infamous report, and most of that can never be reopened, either because of subsequent building or because services would be totally uneconomic and little used. ‘Reversing Beeching’ is a slogan that makes as much sense as ‘Get Brexit Done’ but gosh, it did not half work as a PR exercise.

As for Fleetwood, all it is getting is a £100,000 study to see if it can be reconnected to the network which is all very well but hardly meriting the coverage it received. That did not stop

Shapps, after a morning spent in the studios, traipsing up to Fleetwood for yet more TV coverage. Indeed, the extent of the coverage of such a non-story made me feel embarrassed at my own profession of journalism and angry at the laziness of so many of my colleagues who swallow any excuse to show a few shots of moody 1960 stations and a clip from Brief Encounters.

The one significant aspect of this bit of nonsense is that it demonstrates that the government realises that people care about the railways. Hopefully, that will inform the big decisions that ministers need to make on the railways in the next few months.

A step too far

There is one other aspect of the railways which was contained in the Queen’s Speech but which so far has attracted little attention. The government is seeking to ensure there is a minimum level of rail service during strikes. The intention is to ensure that people can still get to work when there is industrial action on the railways. It is clearly something of a crowd pleaser aimed particularly at the benighted commuters on the various Southern networks who have suffered from several bouts of strike action.

Details, however, are few and far between and any assessment of how it could be done highlights more problems than answers. This is something of a sledgehammer to break a nut. ASLEF, the main drivers’ union, had no strikes last year and has had very few in recent times (not least because they have gained significantly improved conditions thanks to privatisation!). The RMT, run by a weird almost cultish bunch of leftists, is much more prone to strike action but is its members are less effective at stopping services.

Privately, this is the last thing the train operators want. They have enough on their plate without trying to wade through complicated new trade union legislation. They sense that this is not so much to do with ensuring there is a train service for commuters but rather that it is part of a long war between successive Conservative governments stretching back to Heath and the three day week which Boris Johnson would like to won once and for all.

It looks, though, like a step too far and has all the hallmarks of bad legislation such as the Dangerous Dogs Act or the Poll Tax. Forcing people to go to work is not possible in our democracy and imposing big fines on trade unions who refuse to comply would seem to be unworkable. Could they be blamed for people staying at home and claiming for example to be sick? Since the new government has so much on its plate already with Brexit, avoiding this elephant trap would be advisable.